This presentation is on the second day of LTTE 2020, delivered by Jonathon Reinhardt, an associate professor of English Applied Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition and Teaching at the University of Arizona in the USA. I read his articles quite a lot, and it’s super fun seeing him virtually and get the chance to discuss with him.

To start, here’s an outline of what he discussed, in the form of questions for us to start considering.First, how have English, Learning, and Technology changed over the past few decades and how are they changing? Considering these changes, what are the implications for online English learning? Why do people do it, how do they do it, when, where, and with whom? Simply put, no longer exclusively in school because it’s required. In his talk he elaborated on those points and argue that, thanks to developments in digital online technology, English learning is now done not only for both extrinsic but also intrinsic reasons, that it is learned not only formally but also informally, that English is not only consumed by learners but also ‘participated’ in, and that it is no longer only exceptional practice, but it’s everyday practice. He concluded by offering a few formal learning activities that leverage i.e. take advantage of those potentials.

He began his presentation by situating us historically in our current practices. He asked us to think, in the past several decades: 1/ How has the status of English changed? 2/ How has English learning changed? 3/ And how has technology changed? And so then what are the implications for what we understand to be online English learning?

We know that the status of English, that is, what English is, has changed considerably over the past few decades. First, in the 20th century in many places, and still today in some areas, English was understood as a foreign language, something abstract out there, not personally relatable. In the 21st century, however, the Internet is making it a global language, something that serves as means of communicating and interacting not just with people of the English ‘core’ countries like the UK, USA, or Australia, but as a lingua franca with people all over the world. As English becomes global, speakers of it as a first language no longer own the language exclusively.

Second, English was for many merely a school requirement, and it is understood this way in some places still. For those who see it this way, it may be difficult to see its value, especially if it’s presented using old fashioned and boring methods. Things are changing, however, because of its global status, and an increasing number of learners are seeing it as a life requirement not just for school and work, but for doing things that they are interested in doing — following affinities and interests, and becoming a global citizen. This may because in online spaces, learners can see that English is used for daily life, regardless of whether the teacher is watching.

Third, it was seen something optional for social advancement and career success – not everyone learned English, and in some spheres it was possible to get ahead and be successful without knowing English.

Now however, as English has globalized, it has in turn seemed to make it even more necessary for social advancement and career success than ever. Additionally, individuals may be realizing that it has personal value for them. What this means is that over the last few decades, people are developing intrinsic motivations for learning English, not just traditional extrinsic ones. This is something that we should recognize and leverage in our classrooms.

Brad Kachru’s 1985 model of World Englishes captures what many people still intuitively understand about the status of English in the world – that there is an inner circle where English is spoken as a first language, about 380 million users, an Outer Circle of countries that were British and American colonies, about 500 million users, and an Expanding Circle of upwards of 1 billion users of English. It’s important to note, however, that Kachru developed this model before the Internet, and I would argue that in fact the Internet has changed and is changing what English is to people in all the circles, and that it has to do more with economic development and technology more than historical legacy.

When we look at the percentage of the Web by language, we see that English dominates, at nearly 60%, while the next closest, Russian, is 9%. This is a lower number than it has been in the past, but it is still quite a gap. When we look at Internet users by language, we also see that English users dominate. We can also see that Indonesian users also are quite high. It doesn’t, however, show us how many are looking at websites or pages in a language that is not their first language. From this data, we can speculate that people all over the world are exposed to English websites incidentally quite a bit, especially if they want to access information that is not available in their first language.

We also know that English language learning is changing. First, In the 20th century, teachers and formal materials were the source of English knowledge. If we wanted to learn English, we usually learned it in a school. We might have heard it in movies or in music, but they were not participatory, as the Internet is today. Nowadays, English may be also learned informally through observation of, and participation in, authentic social Internet practices, which include popular media, movies, music, and videogames. This has disrupted the status of teachers as the source of knowledge.

Second, when teachers controlled English, learner input could be carefully structured and distributed. Now, however, students have access to more input than a teacher in the 20th century could have imagined. Learners now need autonomous learning skills more than ever to manage their independent learning.

Third, perhaps to justify teacher control, it was theorized that extraneous input was detrimental to learners, because it might not be targeted at their level. For learning to occur, Krashen and other SLA theorists thought, the input needed to be structured at just the right level, and not overwhelm the learner. Now, however, teachers cannot control access, and learners may be exposed to English of all levels, types, genres, and media in many different academic and everyday situations whether we want them to be or not. Second Language Language Acquisition is trying to keep up, and it is turning to socially informed learning theories to explain development.

In sum, English learning has gone from mostly formal, meaning in structured school environments, to both formal and informal, as learners can access authentic discourses and interactions as well as materials designed for language learners, on their own.

There is a lot of incidental exposure to social media and Internet practices in other languages that can be used as a resource for learning. The top block here are social media apps and software – you can see What’s app, Youtube, Dropbox, Twitter, and many other familiar apps and maybe some unfamiliar ones. Most of these apps offer interfaces in the user’s first language, but they may also allow access to content in other languages, sometimes with translation.

The bottom block shows some of the many language learning apps available – one of the largest online markets that there is. These are of varying quality, but there is no doubt that our students are using them intentionally, along with many other more formally-structured learning resources like educational Youtube videos. Learning a language is different these days because of the accessibility of these informal and formal learning resources.

Prof. Reinhart’s third point is that technology itself has changed considerably over time, and that it continues to change. Older technologies for language learning were expensive, specialized, and associated with formal domains, meaning work and academic spheres. Very few could afford to have computer and Internet technology, so workplaces and schools, if they were privileged and wealthy enough, were often the only places learners could access technological resources. Nowadays, technology is more ubiquitous, integrated with our lives, and associated with both formal domains like work and school as well as with informal domains like home, socializing, and play – everyday, personal spaces. With the rise of smartphones especially, digital online technologies have become an almost inseparable part of our everyday lives.

In the 20th century, computer interfaces were often transparent, meaning that to use the computer we had to be able to code and have technical knowledge of how computer logic worked. After the development of graphical user interfaces, however, interfaces are more opaque and user-friendly, meaning that users do not see the ‘backend’ of a webpage or a phone app, and they do not need to know how to code to operate it. The interface of a website or a phone app now teaches we how to use it, in very simple, straightforward, ‘user-friendly’ terms.

It used to be that programmers produced, and users consumed online content. Now, however, after the Web 4.0 shift around the turn of the millennium, users themselves produce, reuse, and share content. This means there has been a shift from specialized production and consumption to everyday participation. Prof. Reinhart believes we should recognize this, and teach our students how to participate critically and productively.

Before going too much further,Prof. Reinhart explained what he mean by ‘everyday. Notice this is one word, and while it can mean something that we do every day, it has an extra meaning. Everyday practices are common, habitual, or routine daily actions and activities—they are dispositional, or ways of doing and being. The everyday can be contrasted with the exceptional, special, or the academic. We associate everyday with the vernacular or the common, average, and unremarkable. We are normally unaware of our everyday practices, and we take them for granted. They become part of what French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called our “habitus” – our daily, unexamined habits and ways of being. Using personal technology and social media has become part of our everyday life, our habitus. Many of us, especially young people, cannot imagine how they would live their lives without it.

Prof Reinhart found some photos online of everyday life in Indonesia with smartphones. It seems like Indonesians are as accustomed to their phones and being online as people in many countries around the world. In fact, when he did some research on what role technology played in everyday life in Indonesia,he found a survey in 2014 had found that Indonesian users spend more than three hours online daily on their smartphones, which is at world’s biggest usage and 39 minutes longer than the average of 142 minutes.

He also found that 94% of Indonesians had smartphones and that Indonesians they spend 8 hours a day on the Internet – this means not just browsing the Web but shopping, using ride share, texting, etc. – He also found that the top google search query was google translate. This leads him to believe that Indonesians are exposed to quite a bit of online English in their everyday technology-mediated lives, and that they’re using translation tools to help them understand it. Indonesians are also downloading a lot of music, accessing youtube, and are on social media like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Whatsapp, and checking the weather. This really is not much different from Americans, except that Americans don’t access Google translate nearly as often.

So returning to our overlapping circles, we can identify the major changes that have been brought about by the Internet. First, English is being learned for not just extrinsic reasons like to get a job or because it’s required, but also for more intrinsic reasons, because there are things written and said in English that people personally want to know about, and communities they want to associate with that use English. Second, learning is not just formal and relegated to schools, but it is happening outside of schools, informally and incidentally, through personal digital devices connected to the Internet. Third, Internet technology itself has changed with the rise of social media, becoming more participatory and everyday in nature. So then what does this mean about where all three of these circles overlap, Online English Learning?

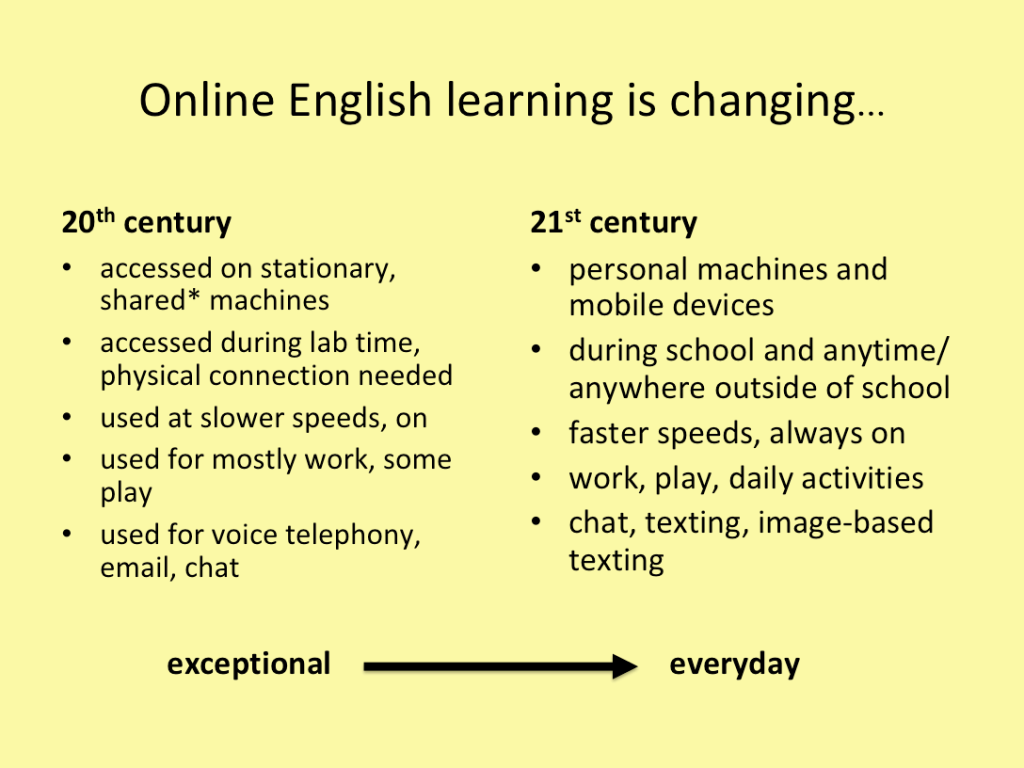

Where the three areas meet leads to one final consideration before we talk about implications, that is, how online English learning is changing overall.

In the 20th century, nearly all online and any technology-enhanced language learning happened on stationary desktop computers. These machines were expensive and so were usually shared and if schools had them, they were in computer labs that were accessed during special sessions. Today, nearly everybody is walking around with a personal, mobile device with the power of a supercomputer, connected to half of the planet – as mentioned before, this means that access to other languages, cultures, and communities is no longer only possible under the guidance of a teacher.

It used to be that English learning with technology happened during lab time, maybe through an expensive connection. This made it exceptional and unique, something not understand as impacting one’s daily life. Now, online English learning resources can be accessed by many learners not just during school but also any time or place outside of school. Although there are still many learners without access, this development is changing what we understand learning is and what it can be.

It used to be that online learning couldn’t easily be in real time, and that we turned it off sometimes. Now, it’s fast enough to support videos, sound, and images, which enhance the learning experience considerably. It can also be on all the time, for better or for or for worse.

Digital technology in the 20th century was used mostly for work, and casual uses for leisure and communications were rare. Now, we use our devices not just for work, but for play and everyday activities, to the point where we can hardly imagine how to do many things without them.

Finally, for communication purposes, it used to be that we called each other on the telephone and talked. We then started using email and then chat to communicate in real time. Now we no longer telephone and speak in real time with each other as much, but more frequently we text each other to interact, in real time and delayed, using multimodality to make meaning in the form of emojis, gifs, and video clips. In short, developments in technology over the past few decades means that online English learning is no longer something exceptional that happens in school, usually on special machines. It still may be this way, but now it is also something that is part of our everyday lives.

So what are the pedagogical implications of these developments? What does this mean for how we design formal English learning activities and devise learning objectives? So in summary, online English use today is practiced for both extrinsic and intrinsic reasons. The implication is that we should focus on developing learners’ intrinsic motivation to learn English, which is more possible than ever thanks to the Internet. Second, online English is learned not only formally but also informally, so the implication is that we develop informal learning skills in our students and help them develop learner autonomy. Third, Internet and social media content is both consumed and ‘participated’ in, so the implication is that we should help develop our students’ Internet participation and digital literacy skills. And finally, online English use is no longer just exceptional but is also everyday, familiar, and personal, which means we should address the development of everyday English usage skills.

Here are some ideas for learning activities:

To take advantage of the fact that people use the Internet to pursue personal affinities, we should design and implement learning activities that encourage this behavior. Intrinsic motivation has been found to keep people dedicated and committed to an activity longer than extrinsic motivators. Intrinsic motivators might be gaining symbolic or cultural capital, finding relational or interpersonal meaning, or achieving autogenous goals, that is, intrapersonal goals the learner set themselves that do not lead to immediate material gain.

Activities that promote affinity behavior and intrinsic motivation might have students follow an int’l celebrity, sports star, or other famous person on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. They might have students participate in an international fan community associated with a movie, a band or performer, a fictional series like Harry Potter, a soap opera or drama, or a video game franchise. The activity might have them pursue a hobby, interest, or other non-academic pastime like fashion, cars, travel, design, cooking, gardening, or dancing. What’s important is that the learner has a choice as to which affinity they pursue and how they do it, and that they reflect on it. Language use and learning is simply the means to follow the affinity – language learning isn’t the ultimate goal.

It’s important that we promote the use of informal online English resources outside of class, and instead of ignoring or just criticizing them, help learners develop the skills to discern how to evaluate them and use them effectively for their own needs. Doing this will help learners build learner autonomy, develop self-regulation and learning management skills, and promote positive learnful dispositions, which are positive attitudes towards learning that help support intrinsic motivations.

To the end of teaching how to evaluate online learning resources, we need to help learners become aware of their own learning styles, habits, and preferences. We need to help them recognize useful and authentic practices to learn from informally, because some websites and communities are more friendly to learners then others. We should help them find and enable English learning support online, for example, how to used closed caption in on Youtube videos, how to use online translators and dictionaries critically, and how to find and use other scaffolds, for example, mouseover apps that can provide an annotation or a translation for a word. We need to teach them how to use translators critically and effectively, instead of pretending they don’t exist. Most importantly we have to develop learners’ critical evaluation skills, so that they can decide for themselves which resources are most useful in the absence of teachers.

When we encourage our students to pursue affinity-driven online activities and help them develop the autonomy to direct and regulate their own learning in these informal contexts, we also need to help them go beyond just watching and observing. We need to develop social media/internet participation skills in English in our students, as this will allow them to experience authentic, meaningful communication contexts that lead to real learning. It will also lead to authentic learning of culture – not by learning about it, but by experiencing it firsthand. Finally, participating in online discourses will help them develop digital literacy skills that will transfer to other contexts, including more formal academic and workplace spheres.

Observing is the first step – students can join a group or visit a site and observe how others are participating – maybe how they post on a discussion board, for example. They should pay attention to not the meaning of what is said, but how it is said, and how people interact with one another. Note what is polite, what is inappropriate, and what is expected. The next step is to visualize and rehearse participation. What kind of response would be more or less appropriate? What would be accepted? What would not, and why? A potential post could be run through a translator to make sure it’s comprehensible. Then, help learners test the waters, just a small amount at first, and to note the reaction. Maybe it’s just a like or an upvote or a retweet, but even a tiny bit of particiption can help the learner feel like they are invested and engaged. Small steps can lead to longer and more meaningful participation over time.

Finally, we need to give learners the tools they need to participate in everyday, casual, and informal uses of language, because if they participate with the formal, academic language we usually teach them, they may not fare well. By teaching them everyday and online language, we prepare them for a global English world that is not just academic but is comprised of many Englishes. We should teach them slang uses, online abbreviations, and differences in formality levels among texts and genres, for example, between a social media post and a workplace email.

To do this we can have learners rehearse or role play doing everyday things online in English. There are several projects learners can do you might be familiar with, for example, planning a trip or vacation, designing a room or a house, putting together an outfit or a wardrobe, or planning a party or event. These require going to various sites and using various apps, and can be done in pairs or groups. They can read, discuss, and write reviews, for example, of restaurants, websites, businesses, movies, music, etc., and perhaps even post them if they are genuine. They can pretend-shop for houses, cars, clothes, and household goods with pretend budgets, and in doing so, they will have to interact with new forms of casual, everyday English — just remember, don’t let them click on ‘purchase’

.

These sorts of activities can lead to the necessary English language skills and autonomous learning skills that learners will need in the future. There’s a lot more to discuss about these kinds of learning activities, but here are a few more points to bring it together – I think it’s a good idea to use social media or a shared space like a blog where students can come together virtually and share their affinities, evaluations, participatory experiences, and everyday uses with each other – discussing and comparing them as they do them.

It’s also important to have learners reflect on the language they use and learn, and to compare it to academic/formal uses. In other words, you have to get them to focus not just on communicating about the content, but also to step back and pay attention to the language they’re observing using to do it – this is crucial for developing critical awareness.

And finally, to really develop learner autonomy and lifelong learning habits, it’s also important get students to reflect on the extrinsic and intrinsic reasons for learning English, and how online language learning is something they can and should do on their own into the future – not because they have to, but because may want to use it for their everyday lives.

In conclusion, students in the future will need to use the Internet and social media in English for everyday purposes. They need to know how to find personal meaning in what they’re doing and to follow their personal affinities and interests online. They need to have reasons to learn English besides the fact that it’s required of them. They need know that they can learn casually and informally, not just because they are being tested, and they should know that online learning allows for that. They need to know how to direct their own learning and make smart choices with regards to the resources they use for it. They need to know how to participate in Internet communities, not just to be observers or consumers. Finally, they need to know how to use online tools for everyday uses, as well as the everyday, non-academic English language used for it.

As the reasons for learning global English change, the means and materials for learning English change, and technology itself changes, our relationships with each other and with technology itself changes. As technology becomes a part of global, everyday life, it offers the means to make English use and learning an everyday part of the lives of global citizens.

I hope you find this article useful for you, guys…